“From time to time he would lift his eyes to that immense face gazing down on him from the wall opposite.”

George Orwell, 1984

A society that is articulated so systematically inevitably runs into conflict when families used to different dynamics challenge the prescribed normality of the system—especially once they enter the school system, where control is exercised most strongly.

Brave New World

“Brave New World” is the most famous novel by British writer Aldous Huxley, first published in 1932. The novel is a dystopia anticipating advances in reproductive technology, human cultivation and hypnopaedia, and emotional management through drugs (soma), which together radically reshape society.

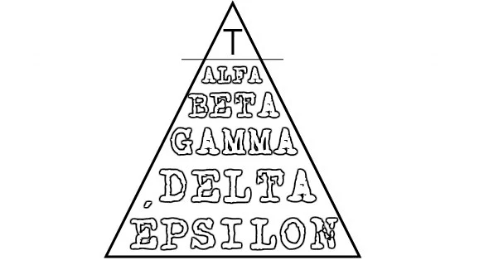

The world Huxley describes could be seen as a utopia, though an ironic and ambiguous one: humanity is ordered into castes, where everyone knows and accepts their place in the social machinery—healthy, technologically advanced, and sexually liberated.

No one escapes the system because it is perfect and it works.

And above all, because the propaganda both produced and consumed makes the people firmly believe they are living in the perfect world. War and poverty have been eradicated, and everyone is permanently happy.

Yet the paradox is that all of this has been achieved by eliminating many other things: family, cultural diversity, art, scientific progress, literature, religion, improvisation, philosophy, love, imperfection…

The Netherlands prides itself on high educational standards and outcomes, confirmed by various international institutions (PISA reports, etc.). Other reports also claim that Dutch children are “the happiest in the world”, and media outlets across the globe echo this message.

The country’s self-promotion is a perfectly functioning machine. The marketing behind it is subtle and relentless, reinforcing a sense of calm and superiority. Never before had I experienced this dynamic of a country as if it were a corporation.

Those of us who have seen other systems often feel a kind of alienation. As my friend says: “Living in the Netherlands is like living in a model village—everything looks perfect.”

Or does it?

Because there are indeed things that don’t work, but the Dutch are unwilling to acknowledge them—for that would mean destroying the image of an idealized place. And ultimately, that would harm the economy, which is the biggest concern.

Laura Basu explains in her article that we shouldn’t be surprised by the chaos in the Netherlands. With elections looming, the country’s image as Europe’s paragon is beginning to fade:

And we all end up buying into this narrative.

The conflict arises when the expat family grows and their children must enter the Dutch school system. Then the bubble bursts, and many foreigners are forced to leave because they run up against a strict, tightly controlled system, where family involvement is undermined by the language barrier. The same happens when families are pushed out of Amsterdam due to lack of space and unaffordable housing prices.

To make matters worse, expat families usually lack extended family support, which means they must rely on daycare—where costs are sky-high.

And here again the Dutch fantasy bubble bursts: the government pays part of the daycare costs, but these subsidies are a double-edged sword, because they are actually loans that the government later reassesses based on family income.

This led, in recent years, to thousands of parents (especially from ethnic minorities) being accused of fraud when in fact it had been a supposed “error” by the state. This oh-so-perfect system harassed and criminalized thousands of families—mostly of Turkish and Moroccan origin—accused of defrauding childcare benefits they had used to look after their children. Many were forced to repay enormous sums, sometimes up to €100,000 within weeks, losing their homes and jobs in the process. Most outrageous of all, they were denied any right of appeal.

“At first I thought it was an isolated incident, but as years went by I saw more and more Dutch colleagues calling me with the same problem. I realized they were being targeted by nationality, and that’s when I brought the case to the authorities,” said Spanish lawyer Eva González, who exposed the corruption.

Of course, no one talks about Dutch corruption. The government made a show of resigning to save face, but remained firmly in place, arguing that it was not an “appropriate” time for the country.

But tolerating is not the same as integrating.

For instance, in this supposedly inclusive, progressive, modern country that claims to respect individualities and identities, the 1985 Transgender Law, while allowing trans people to change their legal gender on birth certificates, simultaneously required irreversible sterilization—a requirement only abolished in 2014, after affecting more than 2,000 people.

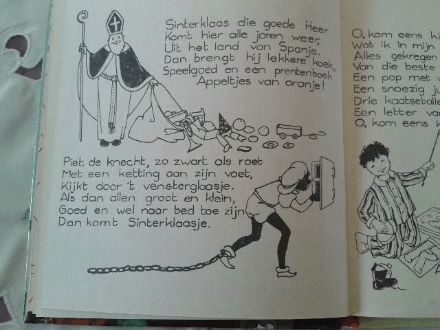

We find not only the racist undertones of the Zwarte Piet tradition (the “Black Pete,” supposedly a humorous figure for the Dutch—once a slave, now Sinterklaas’s “helper”), but also structural and institutionalized racism throughout daily political and social discourse. As Sylvana Simons explains: “Racism in the Netherlands is structural and institutionalized.”

Just two weeks ago we tried to file a bullying complaint against my son’s school, which was itself responsible for the harassment. Not only were we prevented from filing the complaint, but the teacher literally told us: “You should try a school that’s not that white, you know what I mean.”

And we wonder: Why can’t we file the complaint?

Why does the same thing happen to my friend, a victim of domestic violence, who is unable to have a complaint registered by the very police officers who visit her home every time her husband beats her, see the bruises and injuries, and even watch the videos of him hitting her in front of their children—only to label the report as “a family argument”?

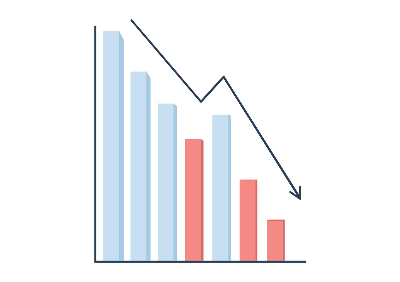

Simply because if there are more official complaints, the national indicators (on violence, education, health—those used to compare countries) go down.

In his country, you don’t say what is really happening.

Of course, I’m not the first to notice this. For those interested, here’s an article explaining why foreigners rarely stay more than ten years.

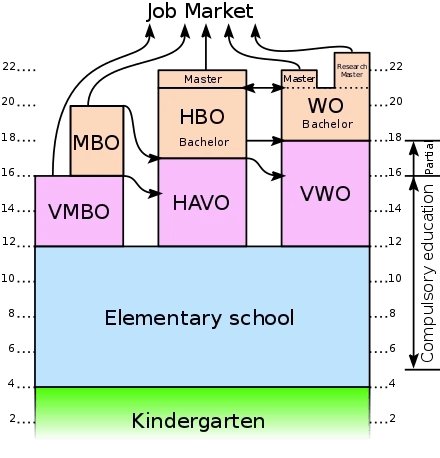

Returning to education: while it may be true that the Netherlands aims to implement “New Age” learning, this goal is far from the reality of its schools. The well-meaning intention of fostering student independence collides with requirements of quality, standardization, order, and competition—imposed through constant grading. From primary school onward, the CITO test scores determine not only students’ future careers and social status but also the amount of money each school will receive from the state.

Public schools therefore select students based on their parents’ credentials, checking the family’s educational background in the hope that they will push their children to achieve above average—ensuring more funding for the school. (I speak from experience: a principal once tried to recruit my son to fill his foreign-student quota, assuring me not to worry about our postal code being outside the district, because he could “fix” the lists.)

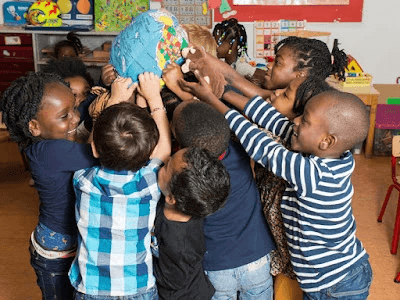

Thanks to this corporate-style system of rewards, “black schools” inevitably arise—those located in poorer neighborhoods, where families (mainly immigrants) have less access to education and thus do not demand above-average performance from their children.

Unsurprisingly, the issue is kept out of sight, and on the rare occasions it emerges, the narrative suggests it is already taken care of, like in this article.

“Doe normaal” is the foundation of Dutch education.

At the same time, the severe shortage of teachers—especially in daycare centers and primary schools (where wages are so low that young people prefer other careers)—has led to the closure of numerous classes and schools. The country’s solution: ask parents to teach. Not just at home, but in the schools themselves. In my son’s school, for example, three parents with no pedagogical training were teaching classes. This has been going on for years (and again, nobody says anything).

To be part of the well-oiled machinery where everyone knows their place—an environment that allows no surprises, a corporate system where flexibility and improvisation do not exist—

Act normal, and you’ll be just crazy enough.